Because February is the month of love, I will be writing

this month’s posts about virtues. Today’s virtue, for no real reason, is

curiosity…

How does curiosity related to both compassion and vocabulary

in young people?

One way is that without curiosity about the world around us,

we won’t learn new words, like what ‘fleek’ or ‘code 9’ mean, and we’ll be

impaired in our interactions with others. That’s maybe bad, although it’s

popular for the older generation to calcify and be unbending about what

qualifies as a ‘real’ word, ‘real’ usage, ‘real’ pronunciation, or ‘real’

music… fashion, art, movies, whatever. Do we want to become those out-of-touch

folks?

I don’t. But that’s less to do with parenting, and

vocabulary in young children. Middle school kids make up their own vocabulary

(or find it online –urbandictionary, btw, is the source and solution for that,

although it seems to be taken over by grumpy old fogies who judge the words

instead of simply defining them, so perhaps soon urbandictionary will be

supplanted by something fleek…) but in order to get to that point, one has to

be able to converse comfortably with the people around about the world around…

… and that comes from having the vocabulary to even think

about it.

Some of the everyday messages our culture sends to kids are

impediments to this vocabulary development.

When kids learn that ‘all noisy kids are bad kids’ they

don’t learn to distinguish in themselves or others the nuances of feelings that

provoke loudness –fury, enthusiasm, terror, grief, excitement, disappointment,

dejection, rage, anxiety, pain, ambivalence, boredom, annoyance, irritation,

aggravation, agitation… All they end up with in the ways to express themselves

to be understood is shouting, feeling ‘bad’ and being ‘upset.’

Without the words, we

can’t think

In a book I read (I really should take better notes) it was

posited that without the vocabulary to think about the world around us and

within us, we are trapped in an internal experience that we can’t describe or

understand, because we simply can’t think about it at all. We think in words.

Without thinking, we

can’t learn

From having the vocabulary that describes what we’re seeing

and interacting with and discovering how we feel about it all, we can broaden

our experience of life to include what others are seeing and interacting with,

including how it seems to make them feel. That is: when we have the vocabulary

to share, we can learn how differently we can see, understand, think about and

respond to the world and our feelings about all of that.

This learning is the basis of compassion.

Without learning,

there is no compassion

When we learn the words to describe our own experience,

internal and external, we simultaneously learn the words others use to describe

their experiences, internal and external.

This is telepathy: the minds joining

in the space between them, to hear and be heard, to understand and feel

understood, to feel and to feel felt

–as Daniel J. Siegel describes in his many books (Parenting from the Inside Out, Mindsight,

etc.)

We can’t do it if we don’t have the words.

The words are made from the world.

The world is here to explore, and human brains are

instinctively attuned to explore, to understand the world around us, from

before we are born as we become familiar with the voices closest to us, and the

sounds they use to make meaning. From there, we race to understand the music,

the words, the sensations, the sights and flavours, as quickly as we can.

What can go wrong if

curiosity isn’t present

When we are with people, in the early stages, who are ‘busy’

doing ‘important’ things –on their phones, with the tv or computer, or silently

in the house or facility—or we spend our days surrounded by people mostly our

own age who are physically watched over by too few adults to interact with

about most of what we’re experiencing, or in environments that are unsafe to

explore (or banned from exploring) we learn what little we can divine mostly by

ourselves, particularly what is happening within us. This desert of curiosity

leaves us without the natural support we need to feel normal in wondering and

asking, and without the vocabulary we need to even form the questions.

When we are with carers who ‘already know’ what’s going on

for us, who we are and what we’re worth –who tell us we’re not hungry when our

stomachs are churning because the clock doesn’t say ‘hungry time’ on it yet, or

that we’re not sad or scared or lonely or hurt when we are, or who tell us

we’re bad people for being alive, making noise, making messes, making poop, or

needing more than they expect us to need, our learning is impaired because our

experience is not what we are told it is. The words we learn don’t mean what

we’re told they mean. This is confusing, alienating and leads to dissociation

from our bodies, and self-loathing.

In each of these scenarios, children grow up without

understanding themselves or their world accurately (or at all), always only

coping and struggling and compensating for what they never got that they

needed. They learn to judge, blame, evade blame, self-medicate, distract and

ignore… themselves and others. This impairs their ability to feel curious about

the world, themselves or others. It is that lack of curiosity that ultimately

impedes compassion, for themselves and others.

Now that we can see clearly why compassion matters so much,

and how curiosity is linked to it, so now we can help our children:

10 Ways to be Curious

and Build Compassion

- Answer questions to the best of your ability, and, when you don’t know the answer demonstrate how to look answers up, how to wonder about their accuracy, and what else might be connected to the subject

- Look up answers you are certain of, because information changes over time and what you learned 15 years ago may not have been true at the time

- Share discoveries you make in your world, whether it’s a way of making your work run more smoothly, a new play strategy in your favourite game, or an ingredient you didn’t know how to use, or a way of driving that makes it safer, or an investment strategy that you’re investigating … curiosity breeds curiosity

- Wonder why others feel or act as they do, and talk about possibilities: what they might be feeling or thinking that leads them to feel that choice is sensible or effective to them

- Notice body posture, gestures, facial expressions and vocal tones around you –on the radio or in movies, or live as you watch the passing parade on the streets, watching from your window or what you see from the car, and describe them: shoulders slumped, big smile, crushed eyes, swagger stride, shaky voice, clipped speech, snappy replies, placid face, touching hair, leaning in, leaning away, et cetera

- Talk about the words for those postures, gestures, facial expressions and vocal tones: dejected, excited, nervous, distracted, depressed, timid, confident, et cetera

- Ask yourself out loud why you acted as you did: what was I thinking? What was I hoping would happen? How was I feeling? What could I have done differently that would have ended up with a different result?

- Observe out loud, in neutral terms (like a camera would record the details, without judgement or evaluation, and without attributing intent or character flaws) what the child was thinking, trying to accomplish, or feeling before they acted the way they did

- Speculate about how you would feel if, or how you did feel when, something happened to you –good or bad: how you would react if you won a lottery, got invited to a special event, lost something valuable, damaged the car, et cetera

- Lead kids to consider how they think they might feel if something amazing happened, or something tragic happened, or if they were where the news report is, or what it might be like to visit astonishing sights like the pyramids in Mexico, or the glaciers in Norway, or Easter Island

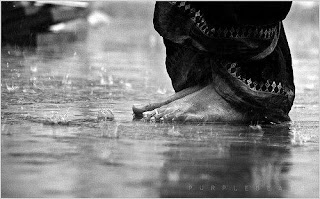

![[Becoming.Number.One♥] by A♥ https://www.flickr.com/photos/zenat_el3ain/3182181634/in/photolist-5RcvJA-4sGR5-9aXY3a-6BzSc1-74p3sr-bJowaB-4WyZhn-wzehf-nbt8Sz-6qTsQD-dYoHf5-F7njUp-mnjaKd-bSSZAz-qjdcA5-kUYPsH-cJhJdE-brt87D-eSmRdt-zU3Jg-a7wBxT-kFkb48-5pQH1B-6jVU7o-q7xHC2-7qXVGD-9sXH4h-sqcQh3-5DSn2j-aDVYNK-dRc7Lz-w8Qmnk-4dhB6M-YhkVFr-9uJ91i-5jCYsS-4mgLwZ-LFKPG-suekp-npoUWi-7JTLC-aL66UP-qYDg43-dfoqz3-ec5r74-Curwec-T7KoQW-74dhyN-48x8sq-koUyur first needs, security and safety, attachment parenting, helping kids feel safe, number one concern](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEif4DYR0JjsoKw-Ovb8CueG_Cg4xWQtC-rLQMVNfkq376WqumaLa15IKXrXeGfwgFi6iPrAqHL4hnzUb7pR58DQK7uTkpSKRwt05y5wECae311fNsnOON2yNGvOmmXcNKijrNNWSXnIy5Q/s320/3182181634_e6b8a24c60_o.jpg)